Reading Time: 10 Minutes

| By Arrow | July 3, 2025 |

What Was the Battle of Saigon?

The Battle of Saigon was one of the major clashes within the broader Tet Offensive of 1968. It took place in the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon and the surrounding areas.

In this battle—like the broader Tet Offensive—the allied forces of South Vietnam and the United States obliterated the North Vietnamese and their southern Vietcong branch (Brenden C. Shannon, March 1, 2024).

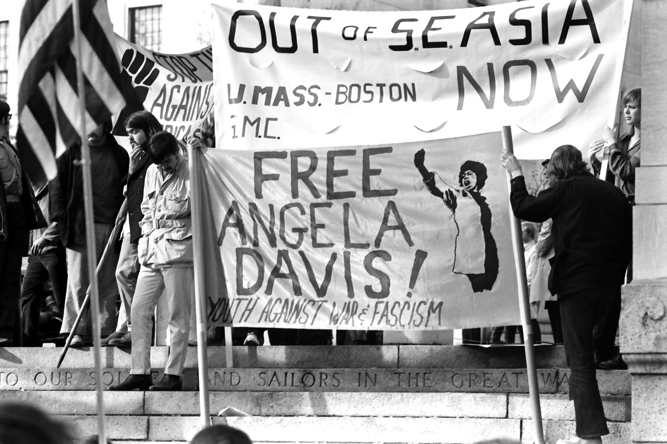

However, the leftist media fanboyed the communists, glorified their failed campaigns, and spread lies about a supposed communist victory. The media buried the successes of the South Vietnamese and American forces in a coordinated effort to sabotage both the Republic of Vietnam and the U.S. war effort.

This brief article provides an overview of the allies’ great victory over the communists—but it cannot do full justice to the gravity of their efforts. It focuses primarily on the Battle of Saigon and does not explore the other battles of the Tet Offensive, which are also essential parts of our history.

Who Were the Warring Parties?

On the allied side were South Vietnam (Army of the Republic of Vietnam, or “ARVN”) and the United States.

On the enemy side were North Vietnam, the Vietcong, and the liberal media.

Interestingly, it was North Vietnam that offered a truce for the Tet holidays—and it was they who violated that truce (Christopher Nelson, February 2019: 15).

How Did It Start?

The Tet Offensive began on January 30, 1968. These early attacks targeted smaller, rural areas. For Saigon and other major urban centers, the attacks began shortly after midnight on January 31, 1968 (“Tet Offensive After Fifty,” Office of the Director of National Intelligence; The Vietnam Center and Sam Johnson Vietnam Archive, Accessed July 3, 2025).

The Tet Offensive consisted of coordinated communist attacks on “thirty-six provincial capitals, five cities, twenty-three airfields, and several other targets” across South Vietnam. It was a massive, ambitious operation intended to overwhelm South Vietnam and force a quick end to the war (Shannon; Sam Johnson Archive).

In and around Saigon, communist forces attempted shock-and-awe tactics with coordinated attacks on key locations, including:

- The Independence Palace

- National Broadcasting Station

- U.S. Embassy

- Cholon District

- South Vietnamese Armored Command Headquarters

- South Vietnamese Navy Headquarters

- Co Loa Artillery Camp

- Tan Son Nhut Airbase

- Bachelor Officer Quarters #3

The initial attacks caused chaos and confusion, sparking intense and brutal confrontations.

With exceptions such as the Cholon District, most Saigon-area targets were retaken by South Vietnamese and U.S. forces within 48 hours—many within hours. Some locations were successfully defended and never fell to the communists at all.

What Were Some Key Moments Throughout the Battle?

The National Broadcasting Station, U.S. Embassy, ARVN Armored Command HQ, Co Loa Artillery Camp, and Tan Son Nhut Airbase were all retaken by allied forces in under 24 hours (Army Times, January 31, 2018; David T. Zabecki, July 26, 2018).

At the National Broadcasting Station, the communists hoped to transmit messages calling for a popular uprising, a collapse of the South Vietnamese government, and defections to the communist side. But South Vietnamese forces had already cut the communication lines, foiling the plan before it could begin.

No uprising ever occurred during the Tet Offensive—despite North Vietnam’s wishful thinking. Within hours of the attack, ARVN’s 1st Airborne Battalion recaptured the station (Sam Johnson Archive).

At the U.S. Embassy, communist attackers initially breached the perimeter, but U.S. forces stormed in and recaptured the embassy within hours.

The Armored Command HQ and Co Loa Artillery Camp were also reclaimed swiftly.

At Tan Son Nhut Airbase, ARVN and U.S. forces—including the 7th Air Force, C Troop 3/4 Cavalry, 377th Security Police, and South Vietnam’s elite 8th Airborne Battalion—fought through the night to defeat the communist incursion.

Nearby, Bachelor Officer Quarters #3 saw intense combat until around 2 p.m., when U.S. tank reinforcements arrived and crushed the remaining communist forces (ibid; William A. Oberholtzer, Accessed July 3, 2025).

The Independence Palace and ARVN Navy HQ were well-defended and never fell. South Vietnamese defenders easily repelled communist attacks there.

By contrast, the Battle of Cholon—within the Saigon campaign—took much longer to resolve. It was one of the fiercest and bloodiest urban engagements.

Cholon was finally cleared on March 7, long after much of the Tet Offensive had been squashed elsewhere. ARVN’s 38th Ranger Battalion fought house-to-house to purge the district (Sam Johnson Archive).

While Cholon dragged on, most of the Tet Offensive was over by February 11 (Naval History and Heritage Command, September 29, 1998).

Some argue that the offensive was decisively crushed as early as January 31 (Nelson: 31).

How Did It End?

Long story short: South Vietnam and the U.S. won—handily.

For our leftist friends, this means that their heroes—the communist North Vietnamese and Vietcong—lost miserably.

By 5 p.m. on January 31, Saigon was “relatively secure,” according to declassified CIA sources (“Summary of Viet Cong Military Activity Up to 1700 Hours on 1 February 1968,” DNI Office, Released January 17, 2019).

By February 2, communist casualties exceeded 10,000, while South Vietnamese and American forces suffered under 500 combined deaths. These figures apply to the entire Tet Offensive (Nelson: 31).

By February 4, only scattered clashes remained in Saigon. ARVN Rangers and Military Police continued to hunt hiding communists. CIA reports noted that allied forces had “regained the initiative” in the capital on the following day (“The Situation in South Vietnam, No. 13,”; “The Situation in South Vietnam, No. 15,” DNI Office, Released January 17, 2019).

By February 7, total communist deaths during the Tet Offensive reached 25,000. South Vietnam and the U.S. suffered a combined 2,054 deaths: 1,303 ARVN soldiers and 703 Americans (“Telegram From the Embassy in Vietnam to the Department of State,” U.S. Office of the Historian, February 8, 1968).

In the end, the communists committed 70,000–80,000 troops, failed to achieve their goals, and lost 30,000–50,000 men.

By every military metric, the Tet Offensive was an abject, humiliating failure for North Vietnam—and, by contrast, “an undeniable battlefield victory for the United States and South Vietnam,” (Heritage Command).

Why Does It Matter?

Why does this battle matter—and why do Americans know so little about it?

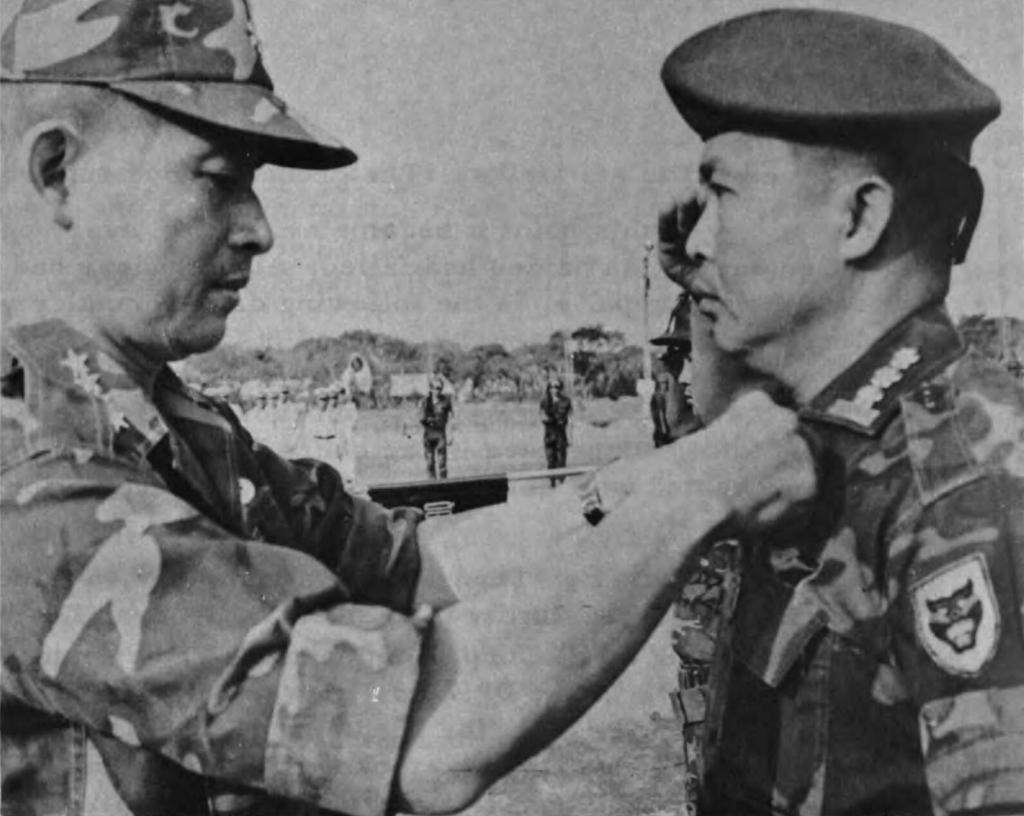

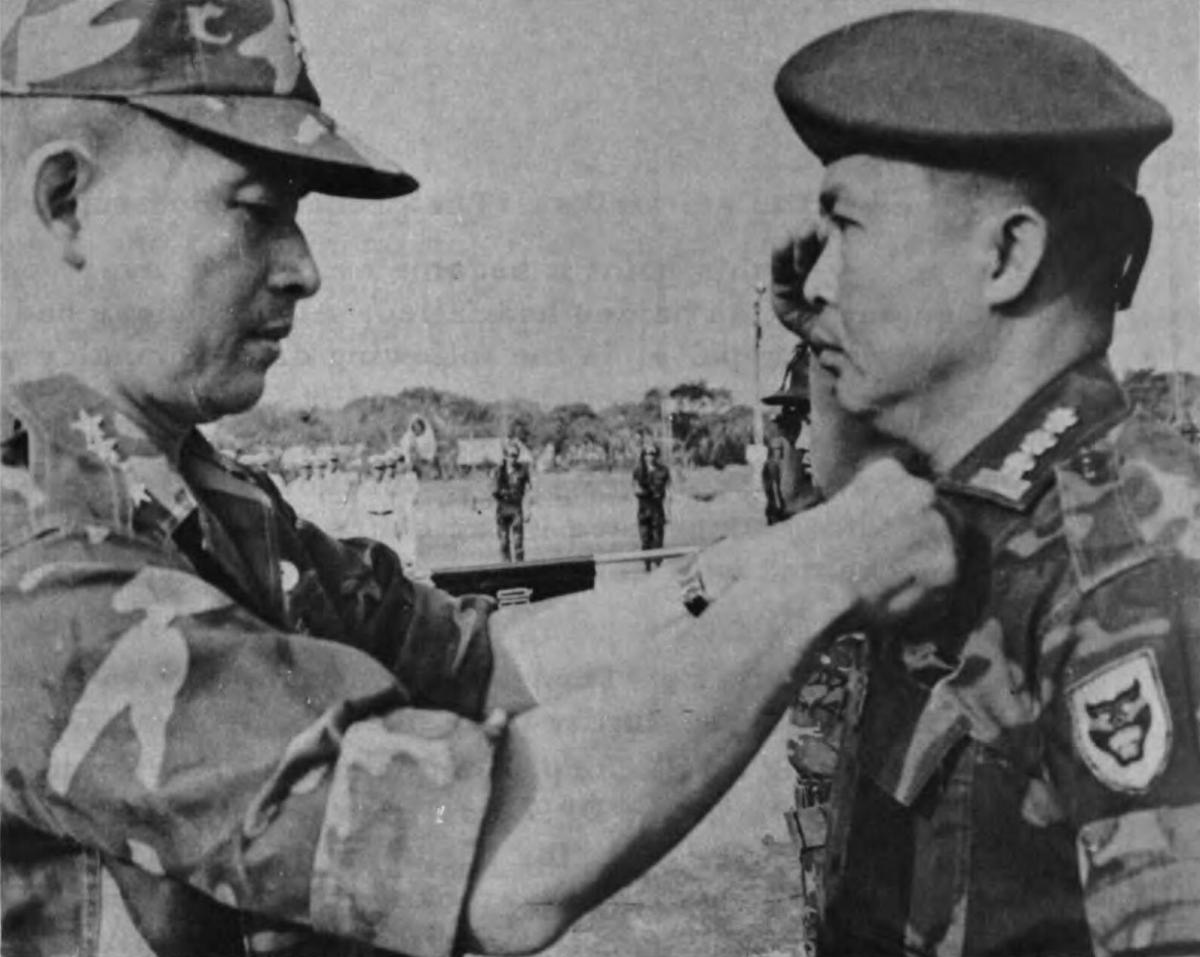

For Vietnamese Americans, the Battle of Saigon is part of our heritage. Those who fought for us are the reason we’re here.

Whether ARVN or U.S. forces, the heroes of that battle kept the Republic alive and saved civilians—many of whom later came to the U.S. seeking freedom for the next generation.

We live because of them. What they did was not only heroic and noble—it was badass.

The fact that so few people know about this is a disservice—not only to those heroes, not only to the overseas Vietnamese community—but to ourselves.

This is great history. This is badass history. This is our history.

And it’s disgusting that leftists, then and now, created and continue to perpetuate an alternate, fake version—glorifying themselves and the communists at the expense of the Vietnamese people, the ARVN, and our great U.S. veterans.

During the Battle of Saigon, liberal reporters falsely claimed that the Vietcong had captured the Chancery building. CBS focused only on the early fighting—when the communists briefly had momentum—and emphasized the damage over the victories (Sam Johnson Archive).

CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite flew to Vietnam to “see for himself,” called South Vietnam “pathetic,” and later presented the destruction as evidence of communist success (Nelson: 32).

After less than two weeks in-country—safely—Cronkite returned home and delivered a grim report on national TV, reaching millions. His coverage was just one drop in the ocean of self-serving, distorted reporting that shaped public views of the war.

Associated Press reporter Peter Arnett later published We’re Taking Fire: A Reporter’s View of the Vietnam War, Tet and the Fall of LBJ, a dramatic self-portrait of a “brave” journalist risking his life for the truth (Associated Press, January 31, 2018).

The promotional excerpt includes scenes of explosions, gunfire, and a nighttime moment where Arnett allegedly steps into the open under fire, yells “journalist,” and makes it to the AP office.

Meanwhile, military leaders like General Westmoreland and Ambassador Bunker are portrayed negatively—Westmoreland “asleep,” Bunker “blindsided” and shuffled to a basement in pajamas.

Cronkite and Arnett are just two examples of how liberals viewed themselves and others.

Vietnam was the first television war—an opportunity for self-conscious, weak men to look brave, despite not being warfighters.

In this distorted view, they were the heroes, the communists were their useful foils, and real soldiers were villainized. This attitude still defines liberal journalism today.

Cronkite and Arnett tried to fabricate danger, but they were not the ones risking their lives. Thousands of allied troops gave their lives in the Tet Offensive—many of them American, even more ARVN.

They were the real heroes. Yet media personalities seized the spotlight. Television gave them power, and they abused it—deliberately misreporting the war and defaming a generation of military men and women.

So, South Vietnamese and American soldiers were sacrificed twice: first in war, and again in how history remembered them.

That’s why so few Americans know the truth about Saigon, Tet, and Vietnam as a whole.

And that’s why this history matters—not only to Vietnamese Americans, but to all Americans.

Not only to those overseas, but to all Vietnamese, everywhere.

We have a proud and powerful history—far more than most of us realize.

The Battle of Saigon is just the beginning. We owe it to ourselves to keep learning, sharing, and honoring this legacy.

Patriots’ Day

And that’s why Patriots’ Day is so important.

This year, we invite you to join us on July 7, to begin a new tradition of commemorating South Vietnamese Patriots’ Day—or simply Patriots’ Day—to remember and celebrate the history and heroes of the Free Vietnamese community worldwide.

Năm sau ở Sài Gòn.

Sources

“AP BOOK EXCERPT: The Tet Offensive’s first 36 hours.” Associated Press, January 31, 2018. https://apnews.com/article/5c292e1a50a545c5b3ab73298782d34c

Nelson, Christopher, “The Power of Information: Reflecting on the Tet Offensive of 1968.” United States Marine Corps University (February 2019). https://www.usmcu.edu/Portals/218/LLI/MLD/Tet%20Offensive%20Case_FINAL.pdf?ver=2019-02-26-152753-987

Oberholtzer, William A., “Looking Back in History: The Battle of Saigon Forty Years Ago.” Tan Son Nhut Association. Accessed July 3, 2025. https://www.tsna.org/documents/14.pdf

Shannon, Brenden C., “Operational Design During the Tet Offensive: The Three-Pronged Approach.” Army University Press, March 1, 2024. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/NCO-Journal/Archives/2024/March/Operational-Design-During-the-Tet-Offensive/

“Summary of Viet Cong Military Activity Up to 1700 Hours on 1 February 1968.” Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Released January 17, 2019. https://www.intelligence.gov/assets/documents/tet-documents/cia/SUMMARY%20OF%20VIET%20CONG%20MILI%5b15561317%5d.pdf

“Telegram From the Embassy in Vietnam to the Department of State.” U.S. Office of the Historian, February 8, 1968. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v06/d62

“Tet Offensive at Fifty.” Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Accessed July 3, 2025. https://www.intelligence.gov/tet-declassified/tet-at-fifty

“The Situation in South Vietnam, No. 13 (As of 8:30 AM, EST, February 4, 1968).” Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Released January 17, 2019. https://www.intelligence.gov/assets/documents/tet-documents/cia/THE%20SITUATION%20IN%20SOUTH%20VI%5b15561326%5d.pdf

“The Situation in South Vietnam, No. 15 (As of 7:00 AM, EST, February 5, 1968).” Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Released January 17, 2019. https://www.intelligence.gov/assets/documents/tet-documents/cia/THE%20SITUATION%20IN%20SOUTH%20VI%5b15561240%5d.pdf

“Tet: The Turning Point in Vietnam.” Naval History and Heritage Command, September 29, 1998. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/t/tet-turning-point-vietnam.html

“The Tet Offensive (Tết Mậu Thân).” The Vietnam Center and Sam Johnson Vietnam Archive, Texas Tech University. Accesssed July 3, 2025. https://www.vietnam.ttu.edu/exhibits/Tet68/

“What happened in the Tet Offensive’s first 36 hours.” Army Times, January 31, 2018. https://www.armytimes.com/news/2018/01/31/what-happened-in-the-tet-offensives-first-36-hours/

Zabecki, David T., “40th Tet Anniversary: The Battle for Saigon.” HistoryNet, July 26, 2018. https://www.historynet.com/40th-tet-anniversary-battle-saigon/

2 replies on “Patriots’ Day Preview: Looking Back at the Battle of Saigon, 1968”

[…] Freedom for Vietnam, “Patriots’ Day Preview: Looking Back at the Battle of Saigon (1968),” Freedom for Vietnam, July 3, 2025. https://freedomforvietnam.org/2025/07/03/patriots-day-preview-looking-back-at-the-battle-of-saigon-1… […]

LikeLike

[…] Freedom for Vietnam, “Patriots’ Day Preview: Looking Back at the Battle of Saigon (1968),” Freedom for Vietnam, July 3, 2025. https://freedomforvietnam.org/2025/07/03/patriots-day-preview-looking-back-at-the-battle-of-saigon-1… […]

LikeLike