Reading Time: 18 Minutes

| By Arrow | October 26, 2024 |

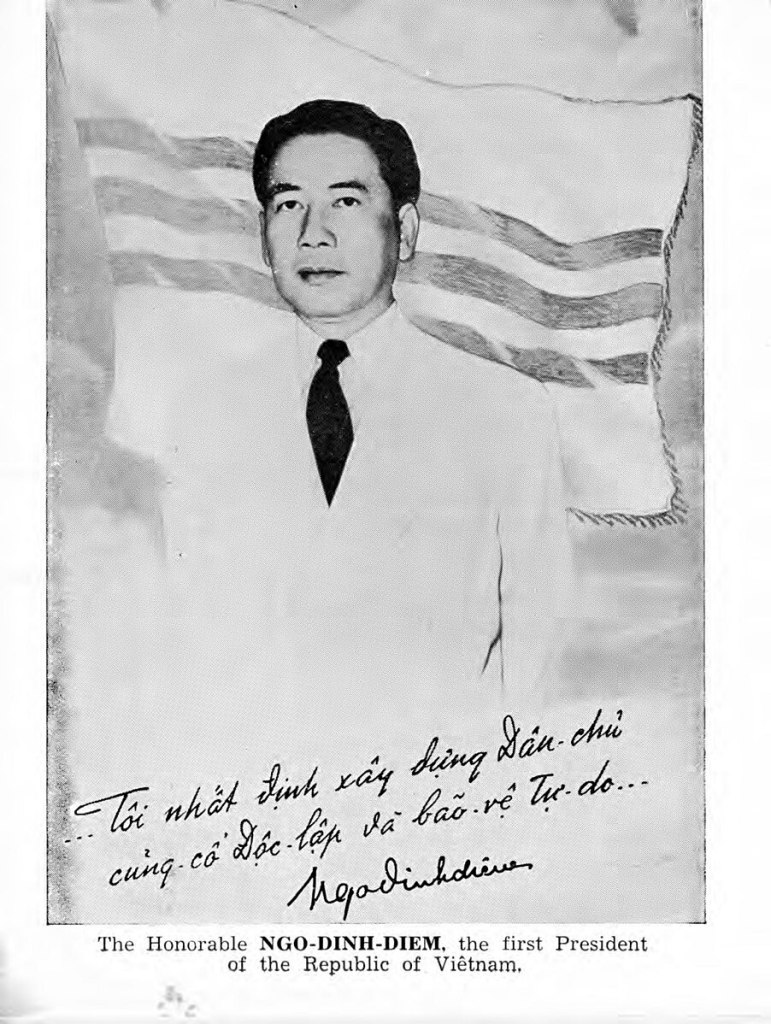

The Republic of Vietnam (popularly known as South Vietnam) officially became a country on October 26, 1955. Its first president was Ngo Dinh Diem, and its governing system was western parliamentary democracy.

President Diem was instrumental in the founding of this country. He faced substantial obstacles, not only from communist North Vietnam, but also from internal enemies, such as the French, the embattled emperor Bai Dai, and rival nationalist sects who did not share Diem’s vision.

Diem would defeat them all on his rise to the presidency. Thereafter, during his nine influential years as President of the Republic of Vietnam, Diem would continue to fight the plague of internal subversion.

This article examines the months leading up to that day in late October, when the Republic of Vietnam, Asia’s great democratic hope during the Cold War era, was founded.

South Vietnam sustained for 20 years. In that time, the nation stunted the rapid spread of Communism through the Eastern Hemisphere, established itself as an economic giant of Southeast Asia, and built a legacy of freedom, courage, and democracy that lives on to this day.

The Geneva Accords of 1954

The Geneva Conference ran from April 26-July 21, 1954. As its name suggests, the conference took place in Geneva, Switzerland.

Parties in attendance included France, the Viet Minh (North Vietnam), the United Kingdom, the United States, the State of Vietnam (pre-republican South Vietnam), the Soviet Union, China, Laos, and Cambodia (“Geneva Accords,” Britannica, 2024).

After several months, a collection of agreements, known as the Geneva Accords, were signed on July 21. However, they were only between the French and North Vietnamese (Britannica). The terms of the agreement were largely dictated by the French defeat at Dien Binh Phu at the hands of the Viet Minh on May 7 of that year (Edward Miller, 2004: 23).

Among other things, the Geneva Accords stipulated that a general election for all of Vietnam would be held in two years, in July 1956. The planned general election sought to unify Vietnam under one government. Two choices would be offered on the ballot. Either Ho Chi Minh and communist totalitarianism, or Ngo Dinh Diem and a Vietnamese brand of western parliamentary democracy (Ang Chen Guan, 1997: 11).

While the agreement seems reasonable on its face, an examination of communist treachery and French duplicity shows that the Geneva Accords were nothing more than a political ploy to ensure a communist takeover of the South. President Diem would rightly denounce and reject the agreements reached at Geneva, and pave way for his own vision of an independent Vietnam.

Communist Terrorism and the Plot to Rig the General Election

There is little reason to doubt that the planned general election, as mapped out in the Geneva Accords, would be nothing more than a farce, rigged by the communists, propped up by the French, and blind-eyed by the feckless “international committee” (officially known as the International Supervisory Control Commission, or ISCC) to ensure a victory for the mass-murdering dictator Ho Chi Minh.

Long before Diem’s rejection of the Geneva Accords, the communists were already conducting a terrorism campaign against the people of South Vietnam.

Deploying their southern agents, referred to by some as the Vietcong, the North Vietnamese used violence and intimidation to disrupt South Vietnamese society. Objectives of communist terrorism included obstructing South Vietnam’s government operations, and discouraging the populace from participating in the country’s democratic process (Geoffrey D. T. Shaw, 2015: 45-47).

Abductions, assaults, mutilations, and murders, often against women and children, were frequent tools in the communists’ terror campaigns (John G. Hubbell, 1968: 64-65). Communist terrorism frequently meant that South Vietnamese villagers faced a grim ultimatum: “submit to the will of the Communists or die a horrible death along with all of your family members,” (Shaw: 53).

As a general practice, the communists routinely violated the terms of the Geneva Accords. They did so brazenly, with impunity (Shaw: 46). Between 1954-55, in direct contravention of the agreement, which they themselves signed, the communists secretly built up their military.

During this timeframe, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) grew from seven divisions to 20, troop numbers skyrocketed from 200,000 to 550,000, and thousands of Chinese and Russian military advisors played significant leadership roles within the NVA (Shaw: 46-47).

The communists had no intention of acting forthrightly if a general election were to occur. In fact, the communists fully expected that an election would not materialize, and had already decided that violence was inevitable (Guan: 12).

At the communist 6th Plenary Session on July 15-18, 1954, Ho Chi Minh was already instructing his followers to prepare for war (Guan: 12). As will be detailed in the next paragraph, the communists only kept the election issue “alive” because it had “great propaganda value.”

There were three major reasons the communists maintained the “diplomatic façade” of supporting a general election in Vietnam (Guan: 13):

- The farce had substantial propaganda benefits, allowing the communists to paint themselves as the “injured party” who was wronged by the South.

- The communist leaders had to put on a show for many of their lower ranking cadres, who naively believed that a general election and reunification were genuine objectives.

- The farce provided an effective smokescreen, shielding the military buildup the North was conducting, as decided at the 6th Plenary Session.

Understanding the communists, their tactics, and their lack of shame, remorse, and dignity, Diem knew he could not rely on them to act fairly or honestly (Shaw: 47). Thus, Diem rejected the Geneva Accords and all its terms. His fearless move was applauded by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower and his administration.

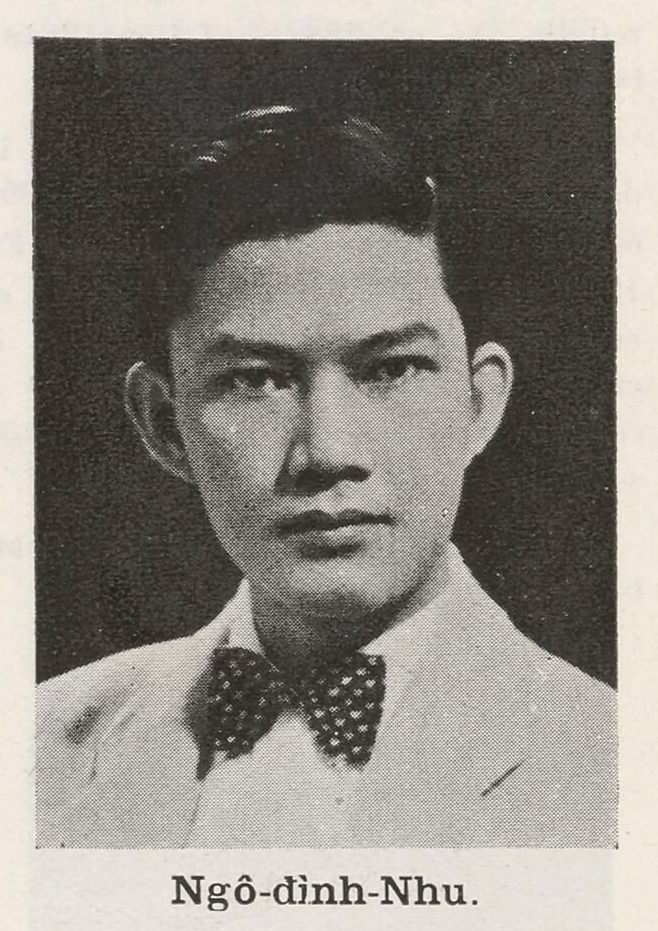

While the French and North Vietnamese colluded to affect a communist takeover of Vietnam, Diem and his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, had other plans. Together, the Ngo Dinh brothers conducted a “political gambit” that saved half of Vietnam from a butchering communist takeover (Miller: 452).

The Ngo Dinh Brothers’ Gambit

This gambit was launched in May of 1953, when Diem departed for Vietnam after a long exile in the U.S. At that moment, the nationalist factions in Vietnam were growing increasingly impatient, frustrated, and mistrustful of Emperor Bao Dai and the French colonialists (Miller: 452).

The French were deceitful and dismissive towards the Vietnamese people. In addition to paying mere lip service to the idea of Vietnamese independence, the French purposely devalued the piaster (Vietnam’s currency at the time). Their deliberate actions exacerbated the economic hardship the Vietnamese people were facing at the time (Miller: 452).

As for Bao Dai, the failing emperor insisted on compromising and cooperating with the sinister French. His version of Vietnamese independence, for whatever reason, always included Vietnam as part of the French Union (Miller: 452).

The Ngo Dinh brothers recognized the deteriorating relationship between the nationalists, Bao Dai, and Bao Dai’s French sponsors (Miller: 452). The opportunity had come. Diem and Nhu made their move.

Nhu exploited the fear and anxiety of the nationalists by rallying the factions at an unofficial “Unity Congress” on September 4-5 (Miller: 452-53). This play marked the beginning of the end for Bao Dai.

The congress itself was not a success. Opening with fierce and unhinged denunciations of Bao Dai, the “chaotic affair” devolved into nonstop bickering and clashing visions between the attendees. In the end, the meeting failed to create any nationalist coalition (Miller: 453). For Nhu, however, the Unity Congress was a political success.

In response to Nhu’s Unity Congress, the nervous and unpopular Bao Dai organized his own event, the “National Congress,” on October 12-13. The event seemed successful at first, with a good turnout that included all the major nationalist factions, except for the Ngo Dinh brothers, who were conspicuously absent (Miller: 453).

From there, the event quickly deteriorated. The nationalist factions rejected all of Bao Dai’s proposals and any suggestions of associating with the French. Ultimately, the nationalists demanded nothing less than pure independence for Vietnam, something that the weak emperor refused to consider (Miller: 453).

Contrary to Bao Dai’s hopes, the National Congress backfired, shedding light on nationalist discontent with the emperor and rejection of his leadership.

After the failed National Congress, Bao Dai had no choice but to warm up to Diem. This frequently meant bending to the Ngo Dinh brothers’ and the nationalists’ demands.

In December 1953, on the order of the Ngo Dinh brothers, Bao Dai fired the despotic and unpopular premier Nguyen Van Tam. Then, in March 1954, again as demanded by the Ngo Dinh brothers, Bao Dai assented to the creation of a National Assembly in the State of Vietnam (Miller: 454).

Ngo Dinh Diem’s Rise to Prime Minister

At the same time, Bao Dai desperately pursued Diem to take on the role of Premier of the State of Vietnam. Widely supported by the nationalists, and popular with the Vietnamese people, Diem suddenly became too valuable for the emperor to lose.

On October 26, 1953, in Cannes, France, Bao Dai floated to Diem the idea of becoming the next Premier. Then, in May 1954, Bao Dai begged Diem to take on the role, pleading, “le salut de Vietnam l’exige,” or, “the salvation of Vietnam depends on it,” (Miller: 454-55).

Eventually, on June 16, Diem finally agreed.

On June 25, Diem arrived in Saigon as the Prime Minister-designate of the State of Vietnam. With this new role, granted on his terms, Diem held “full powers over all aspects of SVN government, military and economy,” (Miller: 456).

Upon his arrival, Prime Minister Diem had many enemies, apart from the communists.

French colonial officials, who did not like Diem, still held significant power in the South Vietnamese government. The Vietnamese National Army, dominated by pro-French, or “Francophile” generals, were also hostile to Diem. He also faced threats from the Saigon police force, who were under the payroll and command of the Binh Xuyen cartel (Miller: 456).

Within 16 months of becoming Prime Minister, Diem would triumph over all of these factions.

The 1955 Referendum and the Fall of Bao Dai

As earlier shown, the French and the communist North Vietnamese came to an agreement at Geneva on July 21, 1954. This agreement was the Geneva Accords, which stipulated that a national election in Vietnam would take place in two years, and overseen by an international committee called the ISCC.

However, also as demonstrated, this agreement was nothing more than a farce. The French and North Vietnamese excluded the South Vietnamese, the U.S., and numerous other parties from the agreement. The French’s track record suggested that neither they, nor the ISCC, had any intention of policing or enforcing a fair and secure election.

Recall that the communists were already breaking all the rules. In addition to building up their army on a massive scale, the communists were conducting a bloody and murderous terrorist campaign in South Vietnam to scare the populace from embracing democracy.

There was no chance that an election brokered by the French, and rigged by the North Vietnamese, would be remotely fair or honest. It was a scam, a fraud, and Prime Minister Diem was well-aware. Thus, the future-President Diem went his own way.

On July 16, 1955, referring to the exclusion of South Vietnam at Geneva, Diem said in a broadcast that South Vietnam never signed the Geneva Accords, and was therefore not bound by it. He made this statement after the communist leader Pham Van Dong declared that the North was ready to start consultations with the South (Guan: 11).

Dong tried to pressure Diem again days later, on July 19, requesting that the Southern leader start appointing delegates for the consultation conference. In response, Diem reminded Dong, on August 10, that the South did not sign the Geneva agreement, was not bound it, and that no consultations would be held between the South and the North. The future president repeated this fact again on September 21 (Guan: 11).

On October 4, Diem pledged that South Vietnam would establish an elected legislative assembly by the end of the year (Guan, 11). Two days later, on October 6, Diem announced that a national referendum would take place on October 23 to decide South Vietnam’s head of state. The choices on the ballot would be either Diem or Bao Dai (Jessica Chapman, 2004: 11).

Sure enough, Diem defeated Bao Dai handily in the referendum. However, some important points need to be understood about this victory.

By the standards of a fully developed and functional democracy, the referendum can hardly be seen as fair. However, in the context of a brand-new country, taking its first steps toward becoming a democratic nation, the election was a success. Despite being under constant threat from terrorism, anarchy, and foreign invasion, the referendum, and how it was administered, fulfilled significant hallmarks of a true democracy.

On Bao Dai’s part, the debauched emperor remained in France for the entire election cycle. He did not come to Vietnam to campaign against Diem, and generally made zero effort to become a serious candidate (Chapman: 32).

In fairness, Bao Dai’s standing among the people was destroyed beyond repair. He had no chance of victory, and everyone knew it, even him. Bao Dai tried to fight back against Diem by firing him as the Prime Minister on October 18, days before the referendum. However, like everything else Bao Dai did, the dismissal failed miserably and had zero impact on the outcome of the vote (Chapman: 12).

Other nationalist factions, such as the Hoa Hao, Cao Dai, and Binh Xuyen, marginalized and relegated to violent thuggery operations, were not legitimate players in this political contest (Chapman: 9).

Given the circumstances, Diem found himself as the only relevant political figure in the country. As the Prime Minister for most of the campaign cycle, Diem had monopoly over campaigning and election administration. He also benefited greatly from Bao Dai’s endless political failures (Chapman: 33).

Diem used all these tools to his advantage unapologetically. In the end, he won the referendum by 98% (Chapman: 13).

Concurrent with his ruthless campaigning, Diem went to great lengths to educate the Vietnamese populace about the western democratic system and how elections worked. Under his direction, the South Vietnamese Ministry of Information disseminated literature to citizens on a broad scale, explaining the democratic process, how to vote, and reasons for national elections and universal suffrage (Chapman: 26).

Diem also routinely released public statements promoting democracy and encouraging his citizens to go out and “exercise one of many basic civil rights of a democracy, the right to vote,” (Chapman: 25).

On the day of the election, novel election integrity measures were instituted.

The vote was carried out by secret ballot, required voter ID, and utilized secured envelopes. Closed envelopes were then quality-inspected by a commission chief, and then dropped into the ballot box. Voting stations were also divided up to accommodate 1,000 voters each, as a means to prevent voter fraud and ballot tampering (Chapman: 31).

Even though Diem was the only viable candidate in a practical sense, he organized a successful election that incorporated many essential tenets of democracy. This was the Vietnamese people’s first interaction with democracy, and the first real democratic election in Vietnamese history (Chapman: 7-8, 24).

Was the election fair by the modern, advanced, “living in safety, stability, and comfort,” standard of the developed western world? No.

Was it a legitimate election that reflected the will of the Vietnamese people? Yes.

Was it a significant moment in Vietnamese history where the Vietnamese people took to the polls and exercised their democratic rights for the very first time? Yes.

The Republic of Vietnam and First President Diem

On October 26, 1955, days after declaring his victory over Bao Dai, Ngo Dinh Diem proclaimed the founding of the Republic of Vietnam, with him as the country’s first president (Chapman: 13). For France, this was the final humiliation, extinguishing any semblance of French power in Vietnam (Chapman: 35).

That day was the start of two invaluable decades of freedom, advancement, independence, and strength for the Vietnamese people, at least in the South.

The legacy this Republic left behind survives to this day, and will continue to echo across time. This legacy may ultimately act as a foundation for a new, free, independent, exceptional, and democratic Vietnamese nation in the not-too-distant future.

Sources

Chapman, Jessica, “Staging Democracy: South Vietnam’s 1955 Referendum to Depose Bao Dai.” (2005). UC Berkeley: Pacific Rim Research Program. 1-52. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/629724zz.

“Geneva Accords.” (Accessed on October 20, 2024). Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Geneva-Accords.

Guan, Ang Cheng. Vietnamese Communists’ Relations with China and the Second Indochina War, 1956-1962. (North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc., 1997).

Hubbell, John G. “The Blood-Red Hands of Ho Chi Minh.” Readers Digest (November 1968). 64-65.

Miller, Edward. “Vision, Power and Agency: The Ascent of Ngo Dinh Diem.” (2004). Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (35:3). 433-58.

Shaw, Geoffrey D. T., The Lost Mandate of Heaven: The American Betrayal of Ngo Dinh Diem, President of Vietnam. (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2015).